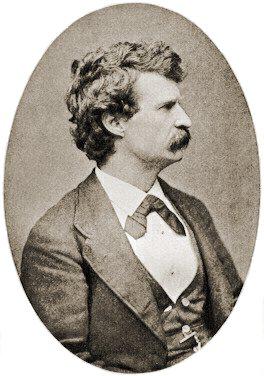

The Chicago Republican, August 23, 1868

LETTER FROM MARK TWAIN.

Mark Twain (Samuel Langhorn Clemens) ONE OR TWO CALIFORNIA ITEMS Special Correspondence of the Chicago Republican. New York, Aug. 17, 1868 We had a pleasant voyage from California. The travel to and fro has diminished considerably, for it has its regular seasons, and the season is over for the present. It will open again in a few months. The exodus of people from the Atlantic States to California within the past nine months, has been something surprising. The ships of the Pacific Mail Company carried 40,000 persons to San Francisco during that time. The ships of the Opposition Line must have carried about half as many. The former company dispatches four steamers a month, and the latter company two. The officers of the ship I came in from the Isthmus said the last was the lightest passenger trip out ward from New York they had had for eight months, and yet they had up ward of eight hundred persons on board. During more months than one, their passenger list reached about 5,000. When I went out in this vessel five months ago, she had 1,200 souls on board, less fifteen. This grand "rush" to California of 60,000 people in nine months provokes little or no remark, now -- but was the "rush" of '49 greater? Several things contributed toward inaugurating this new flight of the people westward. California and Oregon suddenly sprang to a considerable importance as wheat producing States -- the brand of the former taking to itself the chief rank in the Eastern markets and still holding it. Farms could be purchased at reasonable figures in both States. Both climates possessed inviting features. The opening of the great China mail line of steamers, and the rapid advancement being made toward the completion of the Pacific rail road suggested that broad, new fields of labor, capital, and enterprise would be thrown open shortly on the Western seaboard and continue to widen and augment in importance with every voyage of the steamers and every section added to the railway. There were contributors; but the chief contributors to the exodus were the untoward condition of things in the Atlantic States last year, and the reduction of fares on the California steamers. Just in the midst of the sorest distress of the winter, when mills and factories were suspending work and thousands of men were being thrown out of employment just too late to enjoy the eight hour system and the augmented wages they had fought so manfully for, the Opposition line and the regular mail line of California steamers began a system of mutual throat-cutting, in the matter of freights and fares, which has continued to the present time. First cabin fares suddenly came down from $400 or $500 to a $150 -- steerage fares even be low $50, often. It was cheaper to spend three weeks at sea between here and California, than to stay at home. Swarms of men who were idle, and who saw no prospect of employment in the States, found California forced upon their attention all at once. There was a great demand there for workingmen of all descriptions; the wages were excellent; transportation thither was cheap. Sixty thousand men seized up on this inviting opportunity to better their fortunes. The Pacific steamers still carry 3,000 emigrants out of New York every month, and the prospect is good that the "rush" will begin again with the opening of the new season -- say about February. Has the Pacific coast found employment for these people? Yes. For every one that asked it. It can find work for as many more, I think. It need not be supposed that all these emigrants have remained in California. On the contrary, probably half the number, or more, have spread themselves abroad over Oregon, Washington Territory, the British possessions, Alaska, Arizona, Nevada, Idaho, and Montana, and a few have straggled to Japan and China. San Francisco was bewildered for awhile. She found herself besieged by a vast army of unexpected visitors, many of them without a cent, and she did not know what to do with them. As St. Paul justly remarks, in his epistle to the Fenians, "Necessity is the mother of invention." The business men of San Francisco invented the California Labor Exchange. It proved equal to the emergency. For the past six or seven months it has found labor and the customary wages for from fifteen hundred to two thousand immigrants a month -- her full share of the immigration. The others scattered abroad, as I have said. The Labor Exchange not only found employment for fifty, sixty, or seventy men a day, when I left San Francisco, the demand upon it for various classes of laborers and mechanics was greater than the supply. Every "steamer day" (incoming) its offices were crowded with immigrants. They were sent to work in mines, mills, factories, on railroads, and in shops. Yet, still there were orders on the books that could not be filled, as I have just said. With the present light trips of the steamers (500 passengers) the Exchange finds its labors exceedingly light, no doubt. California is a very good State to go to. It is not so speculative a country as it was, in matters of pure business. It has sobered down considerably and taken upon itself the steady-going habits of legitimate trade and commerce. Formerly, to be a Californian was to be a speculator. A man could not help it. One man tried to be otherwise, but he was only kicking against fate. While everybody was wild with a spirit of speculation, and full of plans for making sudden fortunes, he said he would just farm along quietly, and slowly gain a modest competency, and so be happy. But his first crop of onions happened to be about the only onions produced that year. He sold it for a hundred thousand dollars and retired. People who buy San Francisco lots now cannot help being speculators, any more than if they bought Chicago lots; but I mean that wild speculations in candles, rice, mining stocks, and such things, are not nearly so much in order now as they were formerly. The same remark will apply to the sister State of Nevada. The bullion yield of the two States combined, for the present year, will reach $50,000,000, possibly more. At present prices the California wheat crop for the present year would sell for about $60,000,000, greenbacks. California wheat is worth from forty to fifty cents more here, than any other brand, if I read the market reports aright. I have been led to write this chapter, from seeing several flings, in the Eastern papers, at the absurdity of emigrating to the Pacific coast. In view of the fact that the emigrants were about as badly off here, as they could well be, and yet were being furnished with work and good wages as fast as they landed in San Francisco, it seemed to me that the point of order of the Eastern press was not well taken. As far as California politics are concerned, I can only say that everything was promising that the State would go Republican at the Presidential election. Mr. Colfax made himself very popular when he was out there a few years ago, and the fact that he has been so useful an Odd Fellow is something in his favor in a State where that order flourishes so luxuriantly as it does in California. Besides, the election of Gov. Haight was not strictly a Democratic victory. The Republican candidate was very unpopular, even with his own party, while Mr. Haight stood well with all. I wish to talk of this far-off land of California while yet I may. This is the last opportunity I shall have of speaking of it in that sense, for by next May, or at least by next July, it will have been hauled over all the mountains by the locomotives of the Pacific railroad, till it will be so near Chicago that you can see it with a good spy-glass on a clear day. And you can visit it in five days then.

A Railroad Mint -- What the Legend Says This item about railroads suggests that wonderful enterprise, the Panama railroad. We took the train at Panama, clattered for two or three hours through a tangled wilderness of tropical vegetation, and discharged ourselves in Aspinwall. It is only forty-five miles. Going and coming, that little road has carried about 100,000 passengers for the California steamers during the past twelve months -- and charged every soul of them twenty-five dollars fare. About 70,000 of them paid twenty-five dollars apiece in gold; the thirty thousand paid twenty-five apiece, also, but whether it was in gold or greenbacks, I cannot say. One could travel by rail from New York to Chicago -- about 1,100 miles, I think it is -- for less money, when I went over the route last. The road charged them for extra baggage, too. It charges like smoke for freight, likewise. Ten cents a pound for ordinary freights, I am told. It does a heavy freight and passenger business for the French and English lines of steamers in addition. Its stock stands at a premium of 240 in the New York board. It is probably the best railroad stock in the world. It was a hard road to build. The tropical fevers slaughtered the laborers by wholesale. It is a popular saying, that every railroad tie from Panama to Aspinwall rests upon a corpse. It ought to be a substantial road, being so well provided with sleepers -- eternal ones and otherwise. It is claimed that this small railroad enterprise cost the lives of 10,000 men. It is possible. I have been told some things which I will jot down here, not vouching for their truth. The Panama railroad was an American project, in the first place. Then the English got a commanding interest in it, and it became an English enterprise. They grew somewhat sick of it, and it began to swap back until it became American again. The Americans finished it. It proved a good investment. But the right of way granted by the Colombian States was limited to only a few years. The American tried to get the term extended. But they were not particularly popular with the Governments of the Isthmus, and could not succeed. Delegations of heavy guns were sent down, but they could not prevail. They offered a few millions of dollars and Government transportation free. President Mosquiera declined. The English saw an opportunity, now. They made an effort to secure to themselves the right of way whose term was so soon to expire. They were popular with the Isthmian chiefs. They made the Central Governments some valuable presents -- gunboats and such things. They were progressing handsomely. Things looked gloomy for Americans. Possibly you know that they have a "revolution" in Central America every time the moon changes. All you have to do is to get out in the street, in Panama or Aspinwall and give a whoop, and the thing is done. Shout, down with the Administration! and up with somebody else, and revolution follows. Nine-tenths of the people break for home, slam the doors behind them, and get under the bed. The other tenth go and overturn the Government and banish the officials, from President down to notary public. Then for the next thirty days they inquire anxiously of all comers what sort of a stir their little shivaree made in Europe and America! By that time the next revolution is ready to be touched off, and out they go. Very well; two American gentlemen, who were well acquainted with the Isthmus people and their ways, were commissioned by the Panama Railroad Company, about the time of the opposition English effort, to go down to the Isthmus and make a final trial for an extension of the right of way franchise. Did they take treasure boxes along? Did they take gun boats? Did they take other royal persuaders of like description? Quite the contrary. They took down twelve hundred baskets of champagne and a ship-load of whisky. In three days they had the entire population as drunk as lords, the President in jail, the National Congress crazy with delirium tremens, and a gorgeous revolution in full blast! In three more they were at sea again with the document of an extension of the railroad franchise to ninety-nine years in their pockets, procured for and in consideration of the sum of three millions of dollars in coin and transportation of Isthmian stores and soldiers over the road free of charge. How's that? That is the legend. That is as one hears it in idle gossip with steamer employees, about the ship's decks on lazy moonlight nights at sea. I don't know whether it is true or not. I don't care, either. I only know that the American company have got the franchise extended to ninety-nine years, and that all parties concerned are satisfied and agreeable. Mark Twain |

|

| History | Maps | Picture Galleries | Amazing Facts |Panama Railroad Travelogues |

| Quotes |Present | Future | Links | Credits | Site-map |News |